Eating fat to burn fat sounds contradictory, if not nuts, right? The world is full of people who are fat because of high-fat diets, so why would a fit person want to follow suit?

I'm not talking about stuffing your face full of peanut butter cups. I'm talking about following a ketogenic diet—or, put simply, a high-fat, moderate-protein, carbohydrate-restricted diet designed to make the body burn fat for fuel.

Bodybuilders, fitness enthusiasts, and researchers alike have found that such diets are an effective fat-loss tool. In fact, studies have shown that ketogenic diets induce numerous favorable metabolic and physiological changes, including weight loss, less oxidative stress, improved body composition, reduced inflammation, and increased insulin sensitivity.[1-4]

That being said, what does the science surrounding ketogenic diets have to say about individuals looking to run faster or farther, jump higher, or improve other aspects of sports performance? Shouldn't athletes be swilling Gatorade before, during, and after their events instead of adopting a high-fat, restricted-carbohydrate diet?

Ketogenic diets have become increasingly popular among athletes ranging from olympic competitors to endurance runners, with good reason.

Not necessarily. Ketogenic diets have become increasingly popular among athletes ranging from Olympic competitors to endurance runners, with good reason. Let's take a closer look at the science.

What Exactly Is A Ketogenic Diet, Anyway?

Ketogenic diets are very high-fat, moderate-protein, carbohydrate-restricted diets.[5] The exact breakdown of the diet varies between individuals, but a general profile may reflect 70-75 percent fat, 15-20 percent protein, and only 5-10 percent carbohydrate. So, you're probably thinking, all I need to do then is watch out for the carbs, right? Not exactly.

Ketogenic diets are not the same as high-protein, carbohydrate-restricted diets. I often hear people use these terms interchangeably, but the diets differ quite a bit in their metabolism. Even when you've reduced carbs and bumped up your fat, too much protein can actually be a problem.

When it comes to energy, the body prefers to break down fats or carbohydrates for fuel and save protein for other processes, like building muscle. The body can only metabolize a certain amount of protein at one time, so when consumed in large quantities, excess protein has the possibility of being converted to energy, a process called gluconeogenesis. For example, protein can be converted to energy during periods of prolonged exercise, or while exercising in a fasted state. In a ketogenic diet, too much protein could blunt any fat-adaptive responses.

Similar to how ingesting carbohydrates can induce an insulin response, too much protein can also trigger a high insulin response.[6] Some people are shocked to hear this, but protein contains insulinogenic amino acids, or amino acids that spur insulin production, so these amino acids induce a higher insulin release.

Insulin is an important hormone in the body needed to maintain optimum health. It's a key hormone for many metabolic processes. For example, it ensures the necessary cells receive glucose for energy and plays a big role in fat metabolism. However, when insulin is too high, fat metabolism drastically slows down. So, when too much insulin is released at one time—after a very high carbohydrate or protein meal, for example—the body turns to carbohydrate-derived energy as its main source of fuel (glucose), reduces the signal to use fat for energy, and goes into fat storage mode.[7]

Bottom line: consuming too much protein on a higher-fat diet can prevent your body from starting to use stored fat for energy.

It might seem counterintuitive to eat fat if you're trying to use stored fat for energy, but dietary fat does not induce the high levels of insulin secretion seen with a very high-carb meal. Therefore, when the body is relying less on glucose and more on fat for energy (i.e. during a ketogenic diet), insulin secretion is decreased and insulin sensitivity actually increase— an important concept for those suffering from metabolic disorders. Ultimately, this allows the body to continue efficiently accessing fat stores for energy.

Bottom line: consuming too much protein on a higher-fat diet can prevent your body from using stored fat for energy.[8] Protein levels on keto diets are high enough to maintain, and in some cases increase, lean body mass, but a common mistake is to over-consume protein rather than increasing fat intake. The same goes for eating too many carbs on a higher fat diet. To be successful with the ketogenic diet, the majority of your calories should come from fat—not protein, not carbohydrates.[9]

What It Means To Be Keto-Adapted

Fat-adaptation occurs over several weeks when the body switches from using carbohydrates to fat for energy. Keto-adaptation refers to the body's ability to adapt to using ketones—small lipid-derived molecules produced in the liver—and fatty acids instead of glucose as its primary energy sources.[10] Individuals vary quite a bit in how their bodies respond throughout this adaptation phase.

It's not uncommon when adapting to a keto diet to feel a bit more fatigued and sluggish, and have a tougher time getting through your workouts as the body adjusts to a low-carb lifestyle. It takes the body a few weeks to switch to a high-fat diet, and it is this switch that causes the sluggish response. Once you are keto-adapted, your energy levels return to normal and may even be higher than they were on a high-carb diet.

Contrary to the popular belief that certain systems can only use carbohydrates for energy, several major organs, including the brain, are able to adapt quite well to using ketones on a well-formulated high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet.

In addition, ensuring proper calorie intake and electrolyte balance can drastically reduce those initial symptoms. And, even if you do get the so-called "keto flu" during the adaptation period, the effects are short-lived, and they typically pass within the first week or two.

Responses can often reflect how well formulated and maintained the diet is. One often-overlooked component of the diet is ensuring adequate sodium. Sufficient sodium levels can greatly improve symptoms and help mitigate those initial feelings of headaches, lethargy, and nausea.[11]

Contrary to the popular belief that certain systems can only use carbohydrates for energy, several major organs, including the brain, are able to adapt quite well to using ketones on a well-formulated high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet.[11,12] In fact, ketogenic diets are commonly prescribed for the management of epilepsy.[5,13] While the mechanism is unknown, an increase in ketones in conjunction with carbohydrate restriction has been linked with a powerful therapeutic effect resulting in a reduction in seizure activity.

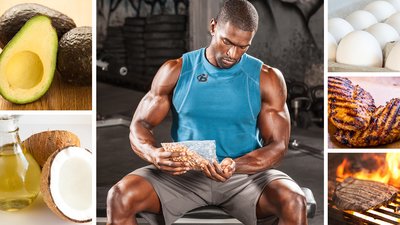

Keto Snack Options

On-the-go snacks require a bit of planning when you're following a ketogenic diet, but there are plenty of low-carb tasty options available. Whether you're looking for something to take with you as you head out the door, or a quick snack you can throw together in your kitchen, here are some great keto-approved options:

- Nuts: Almonds, pecans, macadamia nuts and walnuts

- Cheeses: Mozzarella, cheddar, goat, Swiss, and blue cheese

- Avocados

- Pork rinds

- Deviled eggs

- Cream cheese and berries

- Pepperoni slices

- Cold cuts and cheese roll-ups

- Veggies (green and red peppers or cucumbers) with Ranch dressing

- Celery with cream cheese

Additionally, the body undergoes numerous metabolic changes as a result of the diet. Adaptation to ketogenic diets has been linked with decreases in resting blood glucose, improved insulin sensitivity, lower triglycerides, and increases in HDL levels—all of which would be beneficial for improving heart health and for those with type 2 diabetes.[11,14]

Using Fats For Fuel

In a typical Western diet, such as the "Food Guide Pyramid" diet, carbohydrates constitute the majority of the diet. In these diets, glucose is used as the primary energy source for the body. However, when the body doesn't need that energy, such as during periods of inactivity, a small amount of glucose is converted to glycogen (stored energy) and stored in the muscle and liver, while the majority of glucose is converted to fat.

The average human can only store about 2,000 kcals of energy as glycogen, but can store well over 25,000 kcals as fat.[10] For someone following a high-carbohydrate diet, the only way for them to access this wealth of stored fuel would during periods of increased energy demand, such as during prolonged exercise, calorie-restriction, or fasting.[10]

However, a fat-adapted person is primed to efficiently access this enormous reservoir of energy, preferentially using fat for energy, and fat-adapted athletes are able to rely less heavily on glycogen during exercise.[11]

Benefits Of Being Keto-Adapted

It's clear that ketogenic diets result in adaptations that favor fat metabolism. While the effects on performance have been less researched, a growing number of elite athletes have successfully switched to a low carb lifestyle and maintained their high level performance.

What research has shown so far is that muscle glycogen levels appear to decrease on a high-fat diet during the first few weeks, but the body turns to more efficient utilization of fat for energy, and therefore reliance on muscle glycogen decreases.[8] Hence, submaximal endurance exercise training and performance can be maintained, and in many cases improved, with ketogenic diets. This fact is made evident by the growing number of keto-adapted, elite level, endurance athletes that are thriving in global events and setting course records.[11]

Ketogenic diets have also been shown to improve body composition through both decreases in body fat and increases in lean body mass.

Ketogenic diets have also been shown to improve body composition through both decreases in body fat and increases in lean body mass.[15] Of interest from a resistance training perspective, body composition was found to improve even more so when a ketogenic diet was combined with a lifting program.[2] Most notably, research has shown that these changes can even occur without an athlete having to sacrifice strength as well, in turn effectively favoring an athlete's power to weight ratio.[10,16]

Questions still remain on how the reduction of carbohydrates may affect several aspects related to exercise metabolism and sport performance. For example, the influence ketogenic diets have on high-intensity exercise, power production, supplementation, and recovery is still unclear, but research is active and ongoing in these areas. Further insight into these topics will hopefully expand our knowledge and understanding of these profound and compelling dietary profiles and how they could aid an athletic population.